What convolutional neural networks look at when they look at nudity

Originally published on the Clarifai blog at http://blog.clarifai.com/what-convolutional-neural-networks-see-at-when-they-see-nudity/

Last week at Clarifai we formally announced our Not Safe for Work (NSFW) adult content recognition model. Automating the discovery of nude pictures has been a central problem in computer vision for over two decades now and, because of it’s rich history and straightforward goal, serves as a great example of how the field has evolved. In this blog post, I’ll use the problem of nudity detection to illustrate how training modern convolutional neural networks (convnets) differs from research done in the past.

(Warning & Disclaimer: This post contains visualizations of nudity for scientific purposes. Read no further if you are under the age of 18 or if you are offended by nudity.)

1996

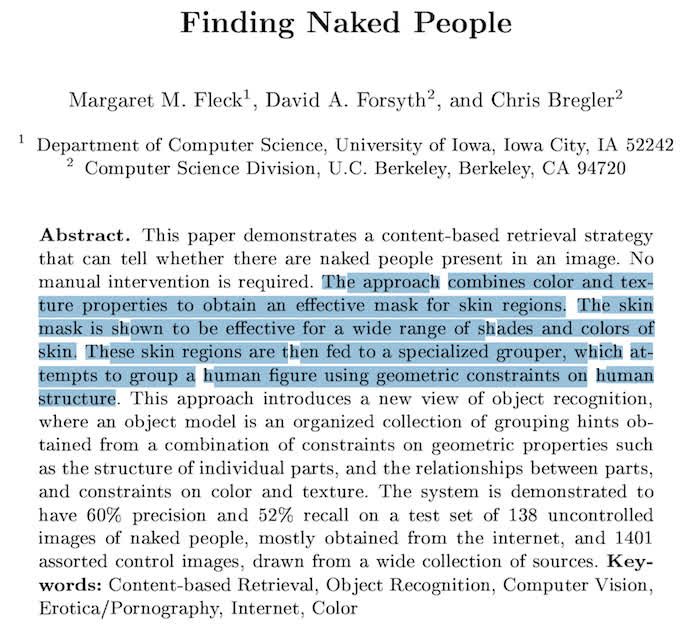

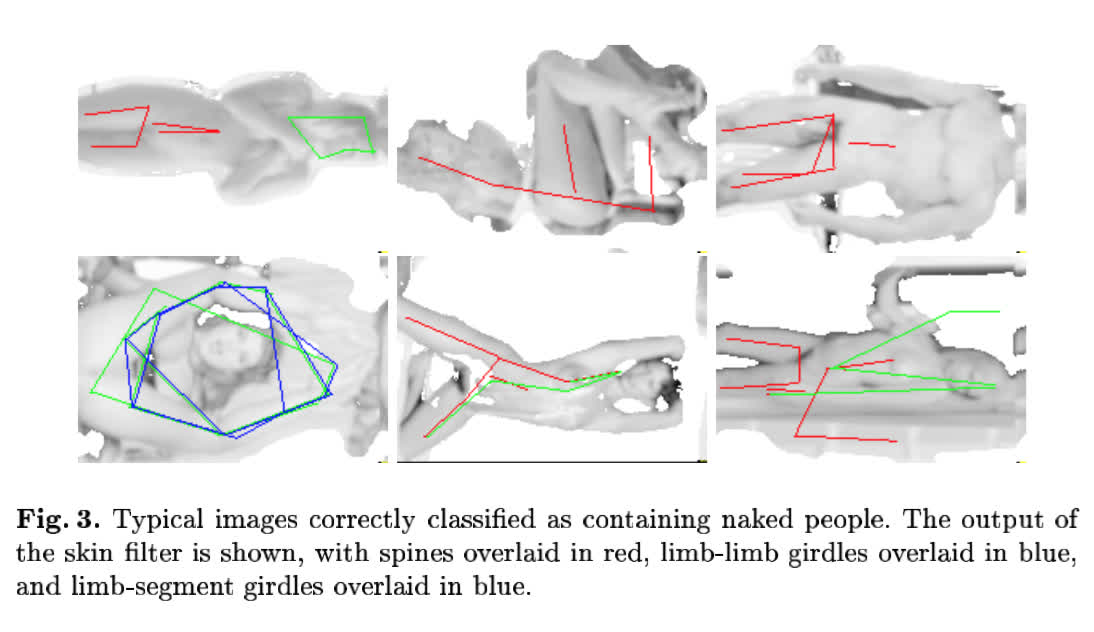

A seminal work in this field is the aptly-named “Finding Naked People” by Fleck et at.. It was published in the mid 90s and provides a good example of the kind of work that computer vision researchers would do prior to the convnet takeover. In section 2 of the paper the summarize the technique:

The algorithm:

- first locates images containing large areas of skin-colored region;

- then, within these areas, finds elongated regions and groups them into possible human limbs and connected groups of limbs, using specialized groupers which incorporate substantial amounts of information about object structure

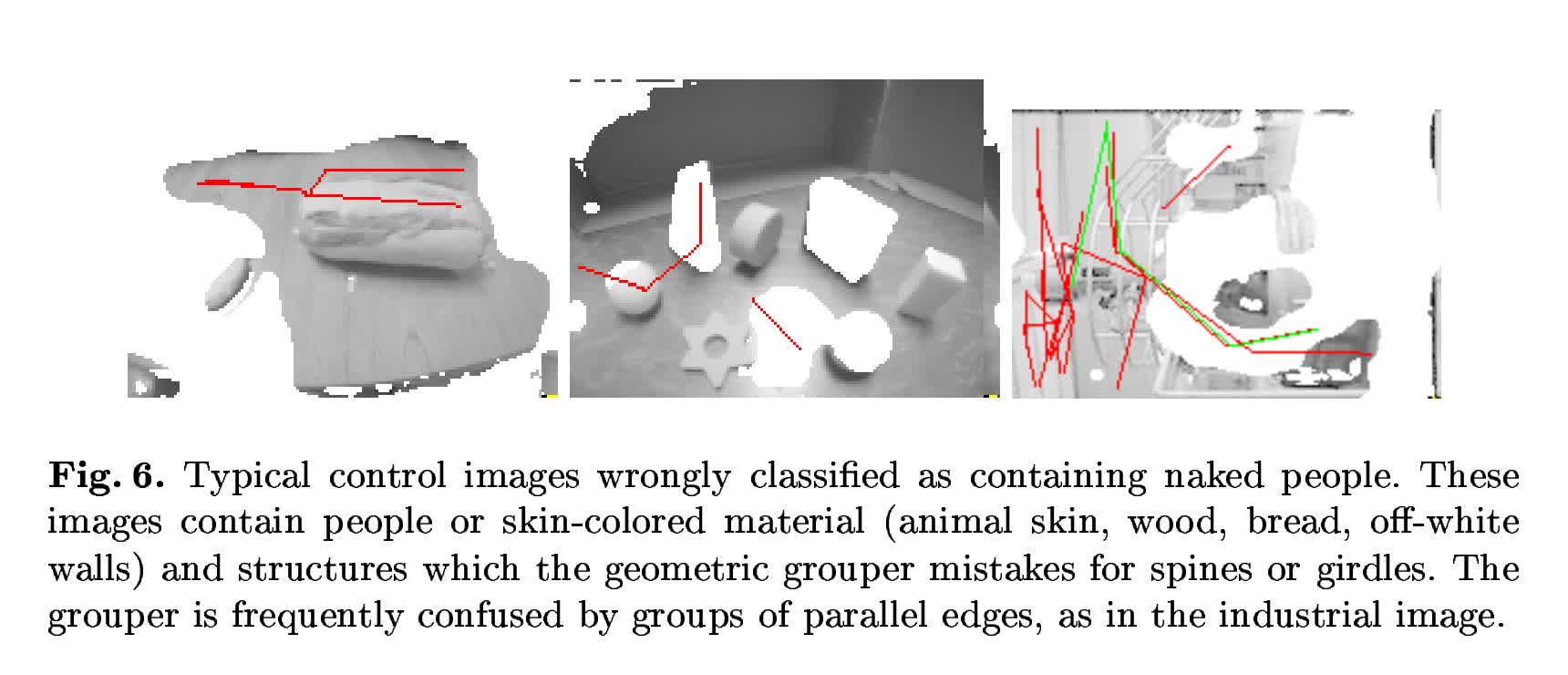

Skin-detection is done by filtering in color space (note: HSV usually works well here but this paper implemented a specialized transformation of RGB) and grouping skin regions is done by modeling the the human figure “as an assembly of nearly cylindrical parts, where both the individual geometry of the parts and the relationships between parts are constrained by the geometry of the skeleton” (cf. section 2). To get a better idea of the engineering that goes into building an algorithm like this we turn to fig. 1 in the paper where the authors illustrate a few of their handbuilt grouping rules:

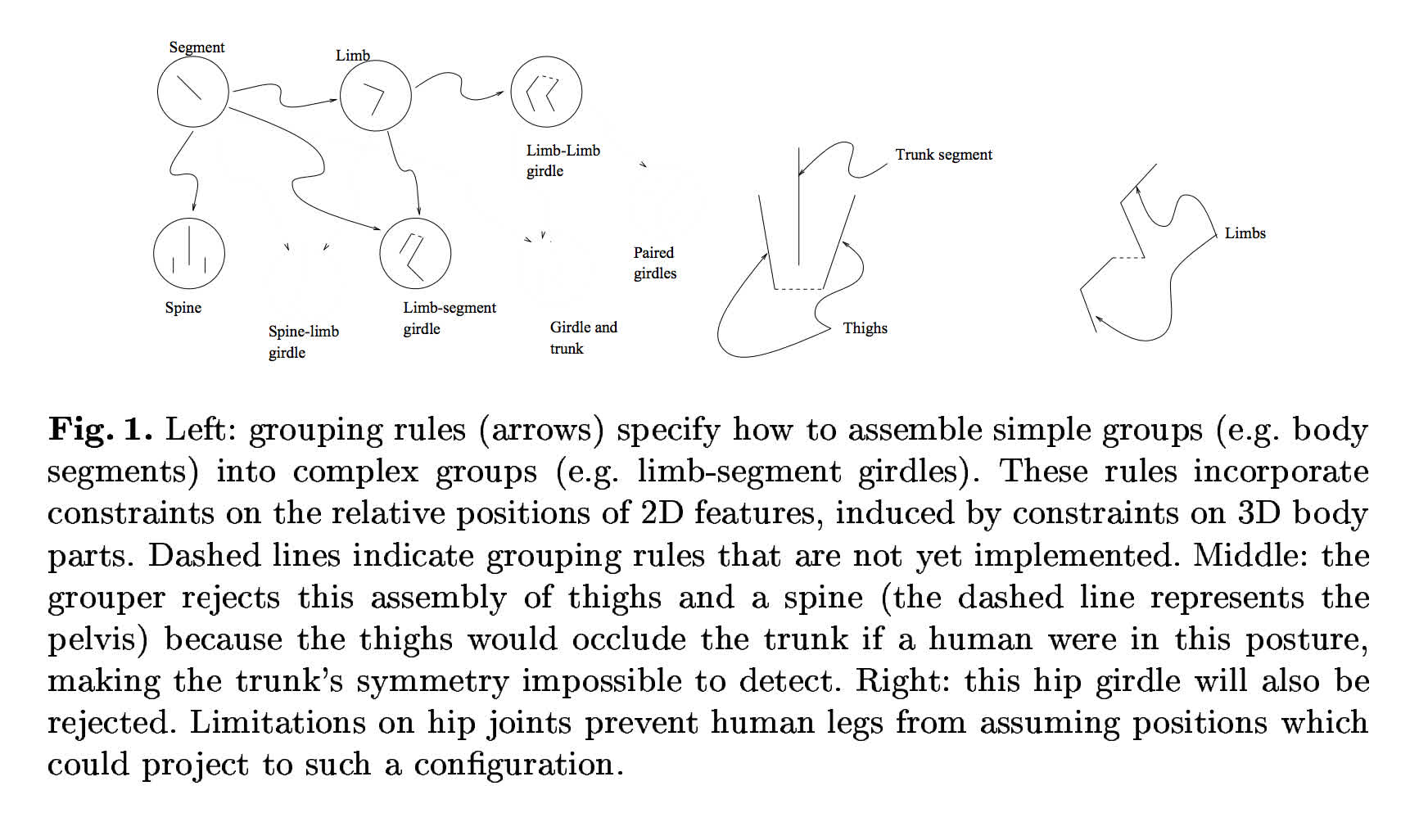

The paper reports “60% precision and 52% recall on a test set of 138 uncontrolled images of naked people”. They also provide examples of true positives and false positives with visualizations of the features discovered by the algorithm overlaid:

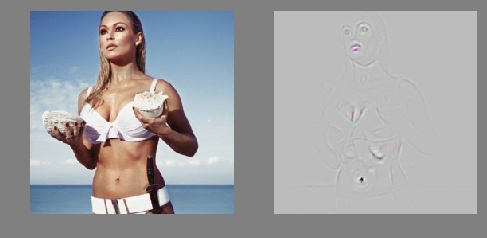

A major issue with building features by hand is that their complexity is limited by the patience and imagination of the researchers. In the next section, we’ll see how a convnet trained to perform the same task can learn much more sophisticated representations of the same data.

2014

Instead of devising formal rules to describe how the input data should be represented, deep learning researchers devise network architectures and datasets which enable an A.I. system to learn representations directly from the data. However, since deep learning researchers don’t specify exactly how the network should behave on a given input, a new problem arises: How can one understand what the convolutional networks are activating on?

Understanding the operation of a convnet requires interpreting the feature activity in various layers. In the rest of this post we’ll examine an early version of our NSFW model by mapping activities from the top layer back down to the input pixel space. This will allow us to see what input pattern originally caused a given activation in the feature maps (ie. why an image was flagged as “NSFW”).

Occulsion Sensitivity

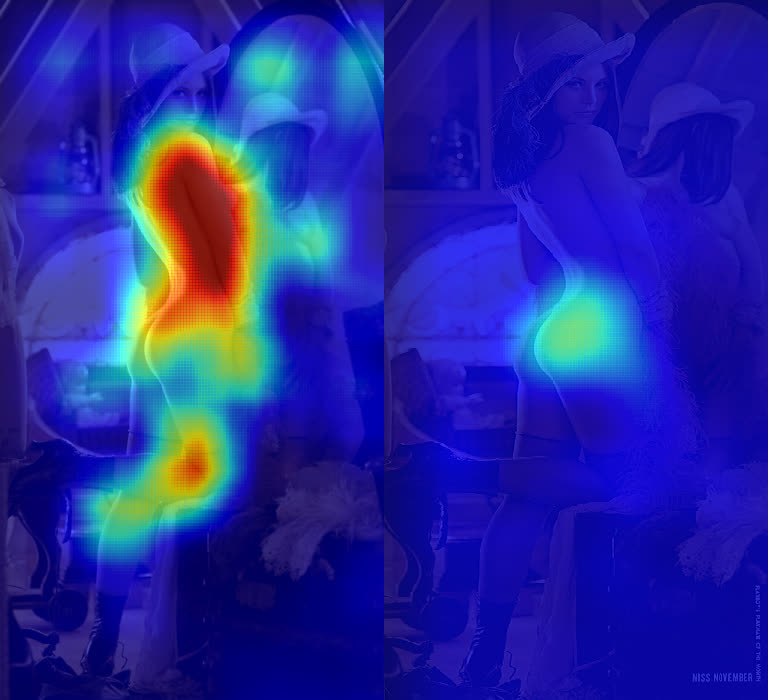

The image at the top of the post shows photos of Lena Söderberg after 64x64 sliding windows with a stride of 3 have applied of our nsfw model to cropped/occuluded versions of the raw image.

To build the heatmap on the left we send each window to our convnet and average the “NSFW” scores over each pixel. When the convnet sees a crop filled with skin it tends to predict “NSFW” which leads to large red regions over Lena’s body. To create the heatmap on the right we systematically occlude parts of the raw image and report 1 minus the average “NSFW” scores (i.e. the “SFW” score). When the most NSFW regions are occluded the “SFW” scores increase and we see higher values in the heatmap. To be clear, the below figures have examples of what kind of images were fed into the convnet for each of two experiments above:

One of the nice things about these occlusion experiments is that they’re possible to perform when the classifier is a complete black box. Here’s a code snippet that reproduces these results via our API:

# NSFW occulsion experiment

from StringIO import StringIO

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from PIL import Image, ImageDraw

import requests

import scipy.sparse as sp

from clarifai.client import ClarifaiApi

CLARIFAI_APP_ID = '...'

CLARIFAI_APP_SECRET = '...'

clarifai = ClarifaiApi(app_id=CLARIFAI_APP_ID,

app_secret=CLARIFAI_APP_SECRET,

base_url='https://api.clarifai.com')

def batch_request(imgs, bboxes):

"""use the API to tag a batch of occulded images"""

assert len(bboxes) < 128

#convert to image bytes

stringios = []

for img in imgs:

stringio = StringIO()

img.save(stringio, format='JPEG')

stringios.append(stringio)

#call api and parse response

output = []

response = clarifai.tag_images(stringios, model='nsfw-v1.0')

for result,bbox in zip(response['results'], bboxes):

nsfw_idx = result['result']['tag']['classes'].index("sfw")

nsfw_score = result['result']['tag']['probs'][nsfw_idx]

output.append((nsfw_score, bbox))

return output

def build_bboxes(img, boxsize=72, stride=25):

"""Generate all the bboxes used in the experiment"""

width = boxsize

height = boxsize

bboxes = []

for top in range(0, img.size[1], stride):

for left in range(0, img.size[0], stride):

bboxes.append((left, top, left+width, top+height))

return bboxes

def draw_occulsions(img, bboxes):

"""Overlay bboxes on the test image"""

images = []

for bbox in bboxes:

img2 = img.copy()

draw = ImageDraw.Draw(img2)

draw.rectangle(bbox, fill=True)

images.append(img2)

return images

def alpha_composite(img, heatmap):

"""Blend a PIL image and a numpy array corresponding to a heatmap in a nice way"""

if img.mode == 'RBG':

img.putalpha(100)

cmap = plt.get_cmap('jet')

rgba_img = cmap(heatmap)

rgba_img[:,:,:][:] = 0.7 #alpha overlay

rgba_img = Image.fromarray(np.uint8(cmap(heatmap)*255))

return Image.blend(img, rgba_img, 0.8)

def get_nsfw_occlude_mask(img, boxsize=64, stride=25):

"""generate bboxes and occluded images, call the API, blend the results together"""

bboxes = build_bboxes(img, boxsize=boxsize, stride=stride)

print 'api calls needed:{}'.format(len(bboxes))

scored_bboxes = []

batch_size = 125

for i in range(0, len(bboxes), batch_size):

bbox_batch = bboxes[i:i + batch_size]

occluded_images = draw_occulsions(img, bbox_batch)

results = batch_request(occluded_images, bbox_batch)

scored_bboxes.extend(results)

heatmap = np.zeros(img.size)

sparse_masks = []

for idx, (nsfw_score, bbox) in enumerate(scored_bboxes):

mask = np.zeros(img.size)

mask[bbox[0]:bbox[2], bbox[1]:bbox[3]] = nsfw_score

Asp = sp.csr_matrix(mask)

sparse_masks.append(Asp)

heatmap = heatmap + (mask - heatmap)/(idx+1)

return alpha_composite(img, 80*np.transpose(heatmap)), np.stack(sparse_masks)

#Download full Lena image

r = requests.get('https://clarifai-img.s3.amazonaws.com/blog/len_full.jpeg')

stringio = StringIO(r.content)

img = Image.open(stringio, 'r')

img.putalpha(1000)

#set boxsize and stride (warning! a low stride will lead to thousands of API calls)

boxsize= 64

stride= 48

blended, masks = get_nsfw_occlude_mask(img, boxsize=boxsize, stride=stride)

#viz

blended.show()While these kinds of experiments provide a straightforward way of displaying classifier outputs they have a drawback in that the visualizations produced are often quite blurry. This prevents us from gaining meaningful insight into what the network is actually doing and understanding what could have gone wrong during training.

Deconvolutional Networks

Once we’ve trained a network on a given dataset we’d like to be able to take an image and a class and ask the convnet something along the lines of “How can we change this image in order to look more like the given class?”. For this we use a deconvolutional network (deconvnet), cf section 2 from Zeiler and Fergus 2014:

A deconvnet can be thought of as a convnet model that uses the same components (filtering, pooling) but in reverse, so instead of mapping pixels to features does the opposite. To examine a given convnet activation, we set all other activations in the layer to zero and pass the feature maps as input to the attached deconvnet layer. Then we successively (i) unpool, (ii) rectify and (iii) filter to reconstruct the activity in the layer beneath that gave rise to the chosen activation. This is then repeated until input pixel space is reached.

The procedure is similar to backpropping a single strong activation (rather than the usual gradients), i.e. computing $\frac{\partial h}{ \partial X_n}$ where $h$ is the element of the feature map with the strong activation and $X_n$ is the input image.

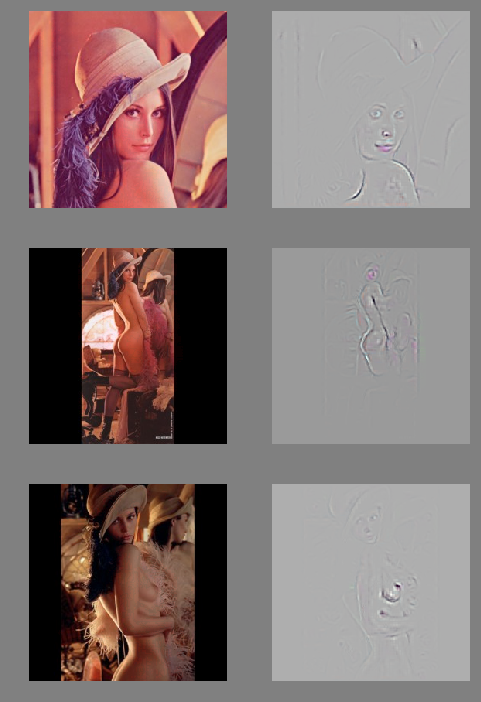

Here is the result we get when using a deconvnet to visualize how we should modify photos of Lena to look more like pornography (note: the deconvnet used here needed a square image to function correctly - we padded the full Lena image to get the right aspect ratio):

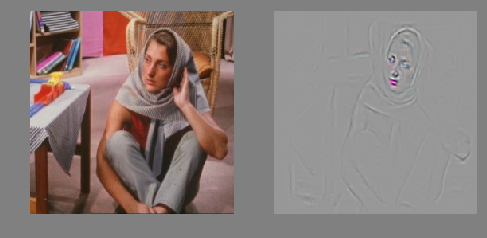

Barbara is the G-rated version of Lena. According to our deconvnet, we could modify Barbara to look more PG by adding redness to her lips:

This image of Ursula Andress as Honey Rider in the James Bond film Dr. No was voted number one in “the 100 Greatest Sexy Moments in screen history” by a UK survey in 2003:

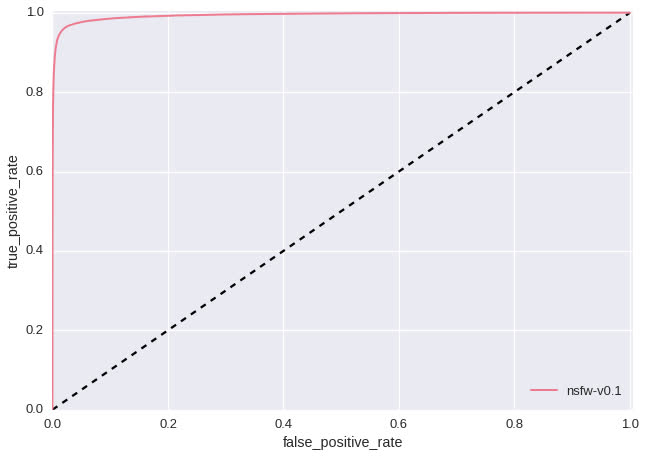

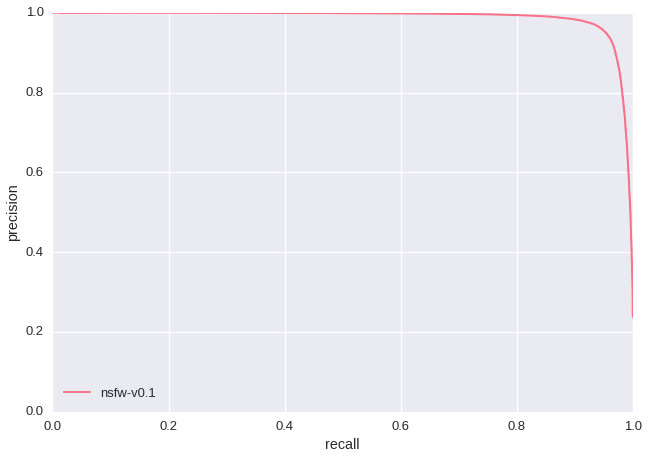

A salient feature of the above experiments is that the convnet learned red lips and navels as indicative of “NSFW”. This likely means that we didn’t include enough images of red lips and navels in our “SFW” training data. Had we only evaluated our model by examining precision/recall and ROC curves (shown below - test set size: 428,271) we would have never discovered this issue as our test data would have the same shortcoming. This highlights a fundamental difference between training rule-based classifiers and modern A.I. research. Rather than redesigning features by hand, we redesign our training data until the discovered features are improved.

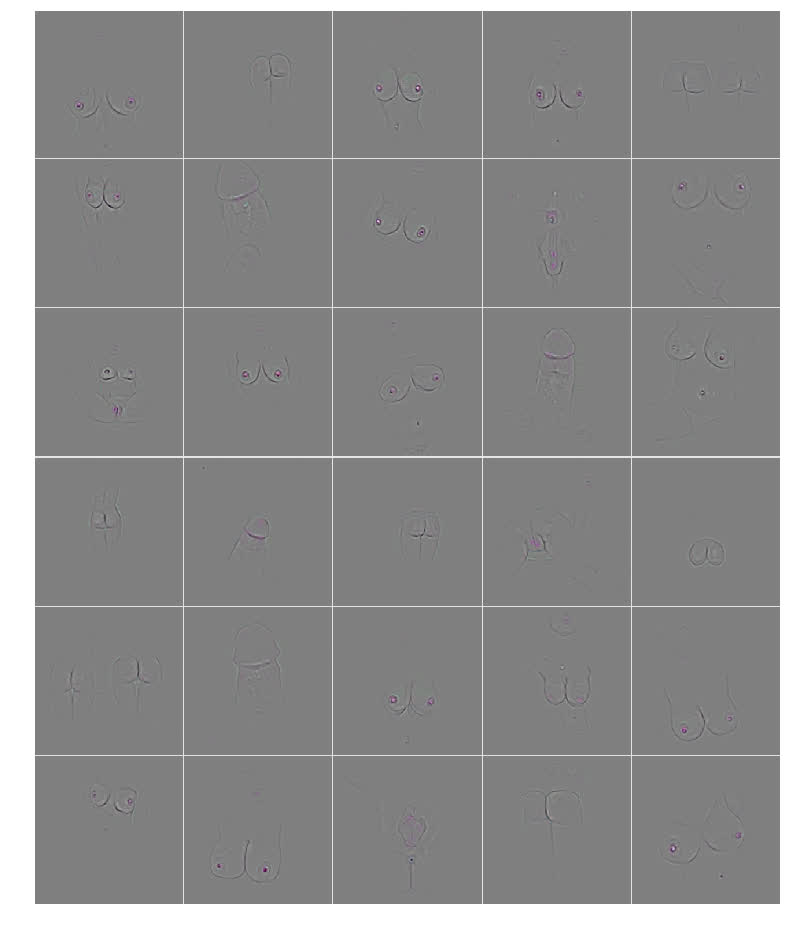

Finally, as a sanity check, we run the deconvnet on hardcore porno to ensure that the learned feature activations do indeed to correspond to obviously nsfw objects:

Here, we can clearly see that the convnet correctly learned penis, anus, vulva, nipple, and buttocks - objects which our model should flag. What’s more, the discovered features are far more detailed and complex than what researchers could design by hand which helps explain the major improvements we get by using convnets to recognize NSFW images.

If you’re interested in using convnets to filter NSFW images, check our NSFW API documentation to get started. https://developer.clarifai.com/guide/tag#nsfw